Four months ago, I decided to create a set of goals based on my friend Kristin Skarie’s book, A Year of Nothing New, in order to live more sustainably. Although this is my final blog post, it is not the end of my nothing new journey. Here is a list of some of my accomplishments and habits that I started, followed by a list of my goals for beyond the finity of four months.

- Stopped buying non-essential new things

- Grew three bean plants in a pot that gave me a total of 40 or 50 beans to eat

- Stopped eating at chains and fast food restaurants and ate at local restaurants instead

- Started tracking my meatless days of the week

- Established better technology and therefore sleep habits

- Avoided disposable plastic

- Used science instead of toxic chemicals as drain cleaner

- Made my own soap

- Detoxed my laundry detergent

- Made things and used second-hand for gifts

- Donated clothes and other things

- Bought and now use reusable pads

- Researched recycling

- Started composting

- Established better shower habits

- Tracked my car versus public transportation usage

- Tracked my time volunteering and working

- Calculated my carbon footprint

- Purchased offsets for a few years’ worth of carbon emissions

- Conducted a cost-benefit analysis for trading in my car

Goals going forward:

- Tool 2 Grow Some Food goals: continue growing beans and then plant tomatoes

- Tool 3 Eat Local goals: look into local farmers markets and eat less meat

- Tool 6 Consume Less Plastic goals: continue to avoid disposable plastic and plan to only buy products with recyclable packaging for a period of time

- Tool 10 Track Your Trash goals: continue attempting to compost and do my waste/water audit again

- Additional goals: work on my college thesis for publishing, look into new jobs, continue climate action including digital climate strikes and pushing for climate emergency declarations and divestment

My final goal was to see how much it would cost to trade in my 2014 Toyota RAV4 XLE for either a hybrid or electric vehicle (EV). Over the past four months, a little under half of which I spent in quarantine, I drove 4,282 miles and purchased 168.2 gallons of gas. By taking the train, I was able to avoid using 50 gallons of gas. The carbon footprint calculators I used last week showed me that the biggest slice of my emissions pie comes from the use of my car, which is why I wanted to consider the possibility of trading it in for either a hybrid or an EV.

I learned how to conduct a cost-benefit analysis when I took economics classes in college, and it is quite complex, but there are simplified versions that anyone can use to weigh options before making a decision. The basic steps of a cost-benefit analysis are to list all of the costs and benefits of the options, monetize them, or convert them into a common dollar or utility amount, and then compare the options in the designated time frame. It generally involves calculations for changes in payoffs and discounting over time, but in my case, I’m just comparing a few of the major costs and emissions.

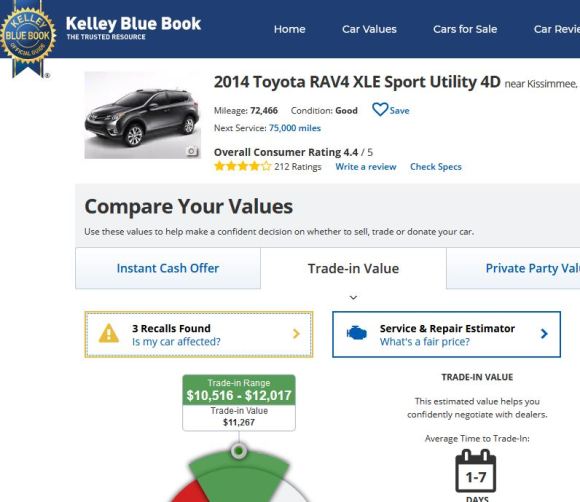

I first figured out the trade-in amount I could get for my current car, which Kelley Blue Book told me is probably between $10,500 and 12,000. My current car is a great car with plenty of room and things I find essential, like a CD player and cup holder that’s big enough for my Nalgene. I like the familiarity of it, so if I traded it in, I would strongly consider a Toyota RAV4 hybrid or EV to replace it. I priced out some used cars on CarMax, and found that hybrid RAV4 cars range from $20-28,000 from the years 2016-2018. The Toyota RAV4 EV was sadly discontinued in 2014, so that’s not really an option unless I get a used one which is older than my current car, which I don’t think I would want to do. I compared the options of LE, XLE, and Limited for RAV4, and it looks like LE is the most basic, cheapest, and desirable for me, even though I currently have an XLE. One of the bonus features my current car has is a sunroof, which is useless to me in Florida.

CarMax conveniently only has one Toyota RAV4 Hybrid LE vehicle, which is 2018 and has 33,000 miles on it. The estimated price is $22,000 without additional costs like taxes, license and registration, and the consideration of how much higher monthly car insurance will cost. To simplify my cost-benefit analysis even further, I’m not going to consider additional costs or even insurance and maintenance costs, and I will instead strictly focus on cost of gas and emissions over the next five years.

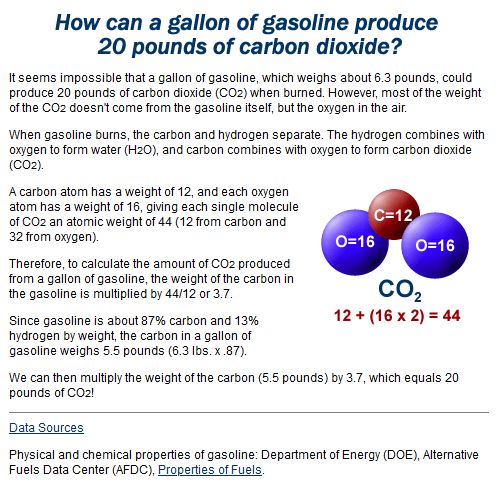

For all intents and purposes, let’s first assume that I will have my new(er) car for the next five years and that the costs of maintenance and insurance for that car are the same as they would have been for my previous car. I get $11,000 for the old car and the new car costs $23,000, so I trade in my car and pay $12,000 up front for the new one. I drive 15,000 miles per year, so after five years, I have driven 75,000 miles. My old car’s average mpg (miles per gallon) was 27.3, so I would have used about 2,750 gallons of gasoline over the course of five years. My new car’s average mpg is 32, so I use about 2,350 gallons, saving 400 gallons of gas. 400 gallons of gasoline produce 8,000 pounds of carbon dioxide, which equals about 3.6 metric tons.

If the average cost of gasoline per gallon over the next five years is $2.50, then I will have saved $1,000 on gas. Subtracting that $1,000 from the $12,000 I paid to get the new car, I still would have invested more than $11,000 for a reduction of 3.6 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions, which is a small amount in the grand scheme of things. Therefore, trading my current car in for a hybrid would honestly cost me a lot more than the environmental benefits are worth. If I invested that $11,000 in renewable energy projects or efforts to halt deforestation, it would probably be put to better use in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

As society shifts toward electrifying our vehicle infrastructure, I expect production of electric vehicles to sharply increase and prices to decrease over the next ten years if we do what it takes to avert climate catastrophe. Until then, I will continue to use public transportation as much as I can and probably drive my current car until I cannot anymore. By the time I need to get another car (if robust public transportation hasn’t advanced far enough yet), I hope that we will have broken free from the stranglehold of the fossil fuel industry and that my next vehicle will be powered by electricity produced by clean, renewable energy. A future of prosperity for the planet and for all people is possible, but we need to fight for it right now, harder than ever. Vote blue in November and may thee use naught new.